Basque

- 15/ 10/ 2001

The Basque language, known as euskara or euskera, has been used since time immemorial in the area around the Pyrenees, through some theories hold that it was once spoken over a far wider area.

It is a pre-Indo-European language, i.e. the roots of some words and the way phrases are constructed date back beyond the Indo-European expansion in which tribes from the north conquered the whole of Europe and extended as far as India.

The lines of research followed to seek out the origins of euskara include the possibility of its deriving from the Berber language of the Atlas mountains in Africa and that of its being related to with remnants of Iberian (which would enable inscriptions on some funeral monuments in the eastern Iberian Peninsula to be deciphered). But none of the hypotheses formed has provided a satisfactory explanation.

There are data which seem to point to euskara being used further north and east than at present. Recent articles lean towards the idea that its western borders were on what is now the natural frontier of Gipuzkoa, so that euskara would not have been spoken in Roman times in what is now Bizkaia. However it is not known what language was used there.

One of the main hypotheses currently under consideration is that the Basque tribes (the Autrigones, Caristios, Varduli and Vascones, and even the Gascons and the Verones) might not have been Basque speakers but rather Celts emigrating through this area.

Place-names may offer more certainty as to the extension of euskara, though precaution is needed here also because, to cite an example, stonemasons from Bizkaia and Alava were renowned and were often hired outside their own areas, so that concentrations of Basque speakers grew up in other regions.

There is little precise information about the use or non use of euskara in the Middle Ages, though it is known that by that period it had been lost in Las Encartaciones. The limits of the Basque language have expanded and shrunk more for economic reasons - its use as a means of communication among merchants -than for political ones. In fact, discounting a very few interventions by state or municipal authorities, there has been little concern until recent times as to whether the people spoke Basque or Castilian. No express mandates prohibiting or persecuting euskara were issued by any civil or ecclesiastical authority until the 20th century. When the Inquisition interrogated witnesses and prisoners in the late Middle Ages they were not condemned for speaking Basque, and were allowed a translator (whose intervention was not always reliable) In the 16th century, and up to the 18th, the church banned dancing, especially within church walls, and admonished clergymen for leading dances, but did not punish them for speaking Basque in their everyday relations with the people (though of course mass was said in Latin).

The situation of euskara in the 18th century is another matter. By that time iron from Bilbao had acquired such renown and the mercantile economy of the area had developed to such an extent that the term bilbo was used to mean "sword", vizcaíno came to mean anyone from the Basque provinces (it is used in this sense in Don Quijote), and people in Gipuzkoa protested, demanding recognition of their identity. Larramendi in his Coreografía de Guipuzcoa and J. I. Iztueta in his Gipuzkoako Dantzak do not identify Gipuzkoa with the territorial frontiers of the modern province, but rather as the area where a particular dialect of Basque was spoken. This is evidence of the use of language as a way of reaffirming the identity of a people and their distinct culture. It also led to the loss for research of those towns in Gipuzkoa where the vizcaíno dialect was (and indeed still is) used.

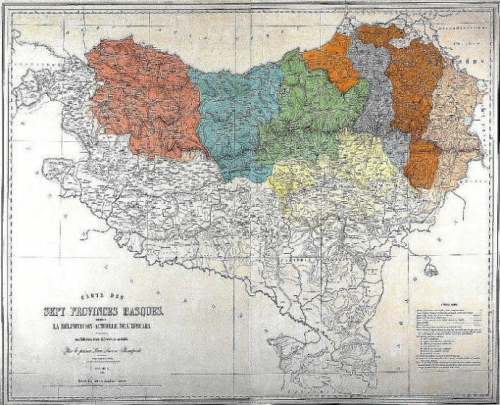

This brings us to the famous language map of Louis Lucien Bonaparte in the early 19th century. Bonaparte's centralist, Jacobin viewpoint led him to limit his studies to a provincial scope, and he ignored or left out any developments outside the frontiers. This meant that, for instance, the part of the Pyrenees in modern-day Aragón (Jaca), where Basque was spoken until well into the 20th century, was not analysed because of his pre-set territorial divisions.

Throughout the 19th century, and still more so in the 20th, economic needs first and foremost and the need for a common language for laws and decrees (which is why the French of the court in Paris overrode more widely spoken languages such as Breton, Aquitanian, Basque, etc. on the one hand, and why Castilian Spanish triumphed on the other) led to a further retreat and devaluation of the common language. Basque was seen as a handicap for occupying certain posts, and its influence became limited to family and village affairs. The educated, in their eagerness to climb up the social scale, lost interest in the language, though they did not completely forget it.

After the Francoist victory in the Civil War of 1936 - 1939 Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa were declared "traitor provinces", and the use of euskara was banned, along with any other cultural manifestation which might question the "unity of the motherland". This turned Basque from a linguistic matter to a matter of state, i.e. a political matter.

Attempts to prohibit popular customs generally spark off a political reaction in the opposite direction among those affected by the measures. In this way euskara came to be an essential part of the political ideas of social organisations. The ban on the language was a heavy blow, and its effect was exacerbated by large-scale immigration of Spanish speakers, leaving euskara in very poor shape. The political opposition to the totalitarian regime of General Franco opened up its activities to encompass all areas, including culture and, within that field, euskara.