Kaixarranka

- Iñaki Irigoien

- 15/ 10/ 2001

The article begins with a description of the modern-day festivities, and relates them to ancient rituals performed to bring good fishing. It goes on to give historical data on the performances in the town and explains the function of these dances associated with the change of steward at the Seafarers' Guild. The dance has undergone major changes over the years, which are explained in the article. Finally, the personality which the dance took on in the 20th century is explained.

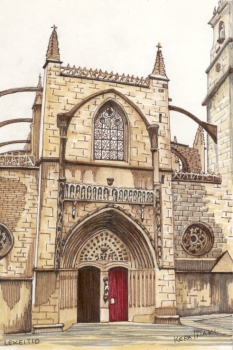

June 29th, the Feast of St. Peter, is an important feast day in the town of Lekeitio in Bizkaia, as St. Peter is the patron saint of the Seafarers' Guild there. Fishing and seafaring in general as a business has declined in the area, but the town continues to mark the feast in remembrance of its past importance.

Music is played and rockets are fired from early in the morning, and they continue as the town authorities walk to mass and during the procession which follows. At that procession the figure of St. Peter is paraded along the quays and streets of the town. At one point in the parade those carrying the figure stop on the quay and make as if to cast it into the sea. This is known as the "Kilinkala", and is mentioned in old records as a ritual in which the saint was asked to ensure that there was good fishing.

After the procession, at around noon, people gather around the old fish market, where the figure of St. Peter stands in a niche decorated with flowers. There, by the door of the market, an old chest is stored which, according an inscription inside it, dates back to the 18th century. A group of seamen take up the chest and hold it shoulder high, flanked by others carrying oars. A dancer or "dantzari" climbs up onto the chest wearing a frock coat over his shirt, and white trousers with a red "gerriko" or sash and white socks. His white rope-soled sandals are cast aside when he climbs onto the chest. In his right hand he carries a red pennant embroidered in gold with the attributes of St. Peter, and in his left he holds a top hat matching his frock coat. The event is accompanied throughout by "txistularis", or flute players.

The first part of the group's journey is short: just a few metres to the figure of the saint. There, the "dantzari" performs the first dances in the kaixarranka, to applause and the Basque battle cries known as "irrintzis". These first dances are a traditional zortziko named after St. Peter, a fandango and an arin-arin.

The group then bears the "dantzari" on the chest through the streets to the home of the chairman of the guild, where the dances are repeated in his honour. After the dance and a little refreshment, the group forms up again and parades to the square, where members of the Town Council stand on the town hall balcony and many local people await them. To the sound of piercing "irrintzis", the kaixarranka is danced for the third and last time. When the dance ends the group walks back to their starting point, where the chest used as a dance-floor by the dantzari is put back into storage for next year. The great traditional significance of this parading of the chest for the guild is explained below.

In recent years the kaixarranka has been followed by a "Soka dantza" or "Aurresku" led by women and young girls, who dance to men whom they choose during the performance. This dance was formerly performed on St. John's day, but was moved to St. Peter's day when the former ceased to be a public holiday. Its name is "Eguzki Jaia", meaning "festivity of the sun", and it is closely related to the summer solstice and its associated rituals. Dances led by women as well as men are mentioned in records dated 1682, and payments from municipal accounts from the 19th century are evidence that they were also performed then.

A look back into the history of the kaixarranka turns up records in the town archives which reveal how it has developed over many years. In the 16th century, from when the earliest records date, the expenses of the Seafarers' Guild are listed as including bulls and dancer to celebrate the feast of St. Peter. The most significant of these records are from a legal dispute between the stewards of the Guild, who appealed to civil law in the form of the Chief Justice of Vizcaya, and the Vicar of the Church, supported by the Bishop of Calahorra. The Vicar complained at the use of ecclesiastical garments and accoutrements by Guild members in lay ceremonies during the festivities in honour of St. Peter. In the accounts of this lawsuit by the scribes and witnesses involved we have reports of how the parading of the chest was performed in the early 17th century. The data provided are from 1605 to 1607.

The festivities and ceremonies began on the afternoon of the Feast of St. John, when Seafarers' Guild members paraded together with the ecclesiastical and civil authorities to a place known as "Aurio", beside the roadside shrine at the entrance to the town. There, discussions were held on how the festivities in honour of St. Peter, patron saint of seamen, were to be arranged. Dances were performed by men and women, as mentioned above. After these dances, everyone walked back to the "nasa" and harbour quayside.

On the eve of St. Peter's Day the dancers were chosen, as were the persons who would represent the apostles: Guild members dressed up as St. Peter, St. John and St. Andrew. From then until July 2nd, they all took part in processions, accompaniments and visits to authorities and local residents, dancing through the streets and in the church or sacristy.

A witness in the lawsuit declared that on those days he saw "seamen dancing with naked blades in their hands and bells upon their legs, with three men bringing up the rear". The middle of these three wore a cape and carried a great key. His face was masked, and on his head he wore a papal insignia as a mitre. The men at his sides wore damask cassocks after the manner of priests, and held wooden sceptres. They were also masked, and wore crowns on their heads.

Various witnesses put the number of dancing seamen at more than twenty, led by a guide or lead dancer, all dancing to the music of drummers. They danced at many times during the festivities, but the most solemn was the dance they performed while the chest was paraded that contained the documents and assets of the Guild, though according to one witness it contained "nought but old papers arising from lawsuits they have had and the rules of the Guild". The chest was taken from the home of the oldest steward to that of the newest. Stewards were usually appointed at around that time every year.

The following description of this parade was drawn up by the scribe Cristóbal de Amezqueta, who certified the manner of the ceremony staged on June 30th 1608. His account includes the following: "at three hours after noon the Seafarers' Guildsmen of this town with their dancers and with them the said stewards new and old went together with the constables and the offers of the regiment of this town and the most honourable men thereof and men from elsewhere, with their dances and drums and the flag of the town", to the home of the old steward, "and when the chest was in the street the young men took it up and a man climbed up thereupon with a pontifical latria upon his head and a mask resembling the visage of an old man upon his face, and upon his back a mantle like that of a clerics, bearing a golden key in his hand, accompanied by two other men, one on each side of the chest, who represented Saint Andrew and Saint John, with their masks and mantles after the fashion of clerics. The said chest was borne aloft amid drums and dancers and mask wearers and other men dressed in disguise running through the streets, with horses and some harquebusiers drawing it on". In this guise they paraded through the streets to the home of the new steward, where the chest was deposited.

In front went the sword dancers, amid much applause from the spectators, as was normal when the Saint was accompanied on solemn processions. The feast of Corpus Christi was another such day. The person dressed as St. Peter took a prominent part in the procession, and went about blessing people from atop the chest. According to witnesses, "many of the unlearned and ignorant did kneel as they passed and beat themselves upon their chests". In other words, they behaved as if this were the real Saint Peter.

A later account by a scribe dated 1655 suggests that it was the statue of St. Peter which was carried on the chest rather than the person dressed up. A ruling passed that year states that the Guild was to be permitted to stage its procession either "with its wooden figure or with a man garbed in cassock and mitre imparting blessings".

Men in capes and masks took part in the event for the last time in 1682. A protest was lodged that year by the Prior of the Chapter because the procession with the men dressed in the guise of St. Peter, St. John and St. Andrew passed "close by the Chapter, and between it and the figure of St. Peter". This suggests that the procession was staged with the statue on the chest and the men dressed as saints on foot. In reply to the protest, the bishop ruled that "laymen shall not don rain capes nor crowns nor sceptres and go about masked".

Another bishop, Pedro de Lepe, was renowned for convening a diocesan synod in Logroño and drawing up a synodal constitution in 1698 which attempted to separate ecclesiastical and civil affairs and banned clerics from taking part in civil festivities. In a document drawn up after his visit to Lekeitio in 1690 and recorded in the parish record book, he made no mention of men garbed as saints, but ordered "that the said chest not be carried in any processional event nor placed in the church as a plinth for the saint", and that "the church Chapter of the town shall not permit the entry in the church of the said chest". This order marked the end of the parading of the Guild chest accompanied by the pomp and circumstance of the chapter house of the church. After that time the civil procession of the chest and the ecclesiastical procession in honour of St. Peter were held separately. Currently, as indicated above, they are held at different times of day.

A description of Lekeitio written in 1740 states that the old way of celebrating the feast day with men dressed as saints came to an end in 1690. This same account mentions the sword dance and the statue of St. Peter on the chest.

The document "Instructions to the Aldermen of the Town Council for Good Government", dated 1822, specifies that a man or boy dances on top of the chest. This is the earliest known reference to the current form of the Kaixarranka: "a man or boy dancing with a flag in his hand".

The second mention found of the dance in the 19th century appears in an addendum by Azcarraga Regil to "Historia de Vizcaya" by Juan Ramón de Iturriza y Zabala. This work was published in 1885, and the addendum describes the statue of St. Peter over the gate to the town which still stood at Arranegi, recalling at the same time the festivity "known by the name of Cacharranca", which means 'dance on the chest'". It is put as being performed on June 30th. The full Town Council in corporation, dressed in the frock-coats typical of their position, paraded to the home of the outgoing Guild steward to fetch the chest, which was then carried shoulder high by four sturdy lads to the gate where the statue of the saint stood. In the presence of the saint, "a dancer dances upon the chest, from which dance the name given to this festivity undoubtedly comes". The procession then continued with all solemnity towards the home of the newly elected steward, where the chest was deposited, with the dance performing constant leaps and steps all the while.

When the old town gate was demolished the statue was moved to its current location, in a niche at the old fish market, and it is there that the first dance in honour of St. Peter is now performed. So from its 17th century status as a ceremony involving important personages, pomp and solemnity, a joint ecclesiastical and civil procession in which everyone took part, the dance has become something simpler involving less people. All that is left of its past is the spectacular nature of the dance itself on the chest - a jewel of Basque folklore - and the symbols borne by the dantzari, which recall a bygone age of the history of the town and of the patron saint of its economic mainstay, the Guild of Seafarers of St. Peter.