Young fellows' associations in Bizkaia (Biscay)

- Josu LARRINAGA. Sociologist, member: EI and EDB

- 15/ 10/ 2001

Conclusion of studies funded by the Diputación Foral de Bizkaia (Charter Council of Biscay), course of 1989-90. This is a detailed report on celebrations, in which groups of young bachelors prepare and carry out their communal festivities.

In his study of organized behavior, the eminent functional anthropologist, Bronislaw Malinowski, establishes a list of universal types of institutions. These include: family, neighborhoods, groups of persons sharing the same sexual gender or age, groups of stigmatized individuals, volunteer or mutual aid associations, professional organizations, groups based on social rank, ethnic stratification, cultural context, or political power.

The life cycles of people grouped according to categories of age (according to birth and infancy, childhood, adolescence and youth, people married a certain year, parents, widows and widowers, the elderly, deceased or ancestors) as well as their rites of passage, usually represent a series of adjustments or changes for that individual with respect to social requirements at each stage.

Additionally, at different festive occasions that exist throughout the year, each age group is assigned certain concrete roles to play (celebratory acts, ceremonies, rituals, etc.), whose objective it is to repeat or to regenerate the cosmic cycle, so necessary for the normal continuity of collective life, or even that of Nature itself.

In this article, we will be talking about groups formed according to age; more concretely, about the associations of young bachelors or young fellows, which were made up of semi-institutional, informal groups of peers, which act almost entirely within the framework of the neighborhood, or auzo.

During the juvenile phase, social consciousness becomes very accentuated, and so does active participation in "loyalty" groups, or those requiring group unity. The characteristics of these juvenile friendship groups vary in number, as do the physical and social characteristics of their components; their duration can be relatively permanent, their sedentary personal interrelations are frequent, and their end may be seen in diverse concretely manifest functions, such as amusement, friendship, cooperation, etc., as well as in other, more latent functions, such as informal socialization. This socialization process may take place through the internalization of group values or ideals, or through the acquisition of those of another reference group. It means a process through which individuals internalize the social and cultural values of their environment, while simultaneously adapting or configuring their own personalities to collective or environmental needs. All socialization processes require the presence of an entire set of media in order to ensure that their members identify themselves with a society's rules, regulations, or values, all of which are rooted in social control. Within this cultural context are the data obtained in our research, which we will summarize below:

The components of these groups, from the area of Busturia (Bizkaia), are called "saragi mutilek" (lit. "the wineskin lads"), a fact from which we may deduce a certain relation with the manner and function of the "eskota" groups. A few years ago, the latter were habitually seen in certain locations in La Merindad de Uribe (Meñaka, Munguia, Arrieta, Larrauri, Emerando, etc.) and Durangaldea (in its hermitage festivities), where youth groups called "eskota" were responsible for buying a (full) wineskin, and inviting the neighborhood for a drink.

Some locations whose feast days (before they disappeared with the Civil War) included such groups of "saragi mutilek" were Ajangiz, Arratzu, Ereño, Errigoiti, Forua, Gorozika, Lumo, Ibarruri, Kortezubi, Mendata, Munitibar, Murueta, Muxika, and Nabarniz. And there was a "good neighboor" relationship between the youth associations in each neighborhood or village.

All of the associated youths were bachelor lads, who entered into the association at the age of about 16 to 18, (or when they first began to wear long trousers), and left the association upon marrying or becoming deceased (as in the case of the "mutil zar"s).

Two members would be youth representatives, called "plaza mutilek" (lit. the "town square lads"), a position which would last for one year, and which had certain specific functions (taking care of festivities, organizing activities, dealing with diverse authorities, administrating funds, etc.).

Upon the arrival of the local or neighborhood feast day, this youth organization would hold a previous meeting, where it would agree on the purchase of a wineskin, payment ("a escote") of the expenses revolving around festivities, the organization of other acts (musicians, collections, etc.), the admission of new members, and the election or re-election of members holding certain posts. Curiously, the system for the election of the Fiel Regidor (lit. Faithful Governor) in Bizkaia was closely related to present systems (universal suffrage, the person leaving the post nominates the person entering the person to enter it, also by lottery, or rotation according to neighborhood or farming estate, or also the selection of recently married proprietors) used to choose youth representatives, and something similar also occurred in the case of many of the post's functional attributes. At nightfall on the eve of the festivities, the young members of the association merrily transported the wineskin, or "zagi edo zaragi", which they had bought "a escote", to a nearby place. During the festivities, the wineskin was usually kept either in a storeroom (ganbara) at City Hall, in a place next to the hermitage or church, in a tavern or private home, or in the oven of a farmhouse (labe). Festivities ended with a common supper (where the main dish is usually codfish), where part of the festivities' wine would be consumed.

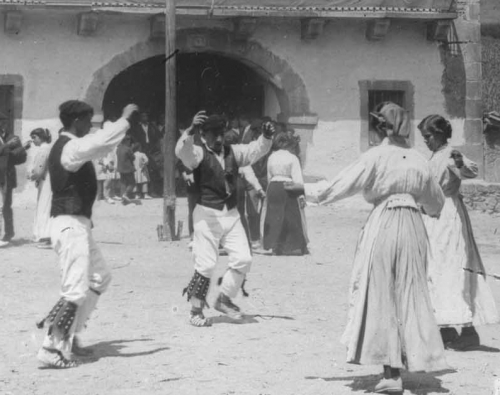

The morning of the celebrations, mass was said in honor of the patron saint, and then the typical morning celebrations were organized. In the afternoon, after the "saragi mutil" of the diverse neighborhoods and surrounding villages have gathered together, there was a dance to the sound of the town's drummer.

Incidentally, before the popularization of group dances such as the "jota", "fandango", or "arin arin", and couple dances such as the "pasodoble" or waltz, it was common practice on Sunday afternoons or feast days for people to entertain themselves by dancing successive "Soka dantzak"s or "Aurresku"s.

In the public square or in front of the hermitage, the local "saragi mutil" began the "Erregelak" (lit. the rules), or "Aurresku of Anteiglesia". The next "Soka dantza" would be one taken by the "saragi mutil" from another town, as would previously have been agreed with its "plaza mutil" or municipal authorities. Thus, according to customary law, the intention was to create harmoniousness among the youths of the area. In many of the village fêtes in the Euskal Herria area, when the "Soka dantza" is carried out, it was done so by reciprocal invitations or successions of groups, established according to gender, age, neighborhood, or area. This can be seen in the lands of El Duranguesado (Garai, Berriz, etc.), as well as those described in Gipuzkoa by Iztueta (Gizon dantza, Gazte dantza, Etxe Andre dantza, Galaien esku dantza edo Neskatxeen esku dantza), or in "Iantza luze", which talks of different neighborhoods in Luzaide.

This modality of "Erregelak", is presently alive in some locations in La Merindad de Durango (Garai, Berriz, Iurreta....) and, it seems, it once extended to and produced variations in the area of Gernika. In this vein, Don Segundo de Olaeta indicates that the oldest version is, indeed, that of the Gernika area (although, he says, the Berriz dancers use mostly a rhythmic scheme of 5/8 time, thus putting their own stamp on the dance), since it coincides with the continuous 2/4 of the dance with a "soinu zaharra", as collected by Iztueta under the denomination of "San Sebastian" (and to a certain extent, also coincides in its lyrics). In Berriz, the elderly, in singing their "Erregelak" lyrics, used the melody belonging to villages nearby Gernika. Azkue, in referring to the "Aurresku" points out: "El 'zortziko',which is now played at the beginning, used to be played at the end, when the 'aurresku' and 'atzesku' did the 'dance of the cockfight', or 'oilarruzka'. The first piece [which has been played since about 80 years ago, and should be played just about anywhere today] is the music to 'Ardoak parau gaitu dantzari' ". He also considers it to be older than the "Aurresku" familiar in his day, and points out the fact that, in Gipuzkoa, this melody was thought to have been originally from Bizkaia.

Referring to this old and forgotten "Aurresku of Anteiglesia" or "Erregelak" (it dates back to the start of the 19th or even the 18th century), it should be mentioned that it reached both extremes of El Oiz (Durangaldea and Busturialdea), and a great deal of the task of keeping it alive in both areas was done by the "Patxiko"s of Berriz dynasty. Additionally, we have found that the vehicle for its musical conservation have been a series of schooled and unschooled "txistulari"s, and a group of eldery "dantzariak" or "aurreskulariak", who remembered the melody, or could associate it with the lyrics. All of this has contributed, to some extent, to its gradual diversification or, simply, to its deterioration over the passage of time.

When the youths from the diverse neighborhoods or municipality had finished carrying out each "Aurresku" or "Erregelak", they would then go up to a garret or attic with the girls who had been invited to the "Soka dantza", and take a swig of wine from the wineskin (generally, the girls were offered the wine diluted with sugar-water), served by the "plaza mutil". Then, they passed the wine around, in jugs (pitxar), and it drunk by those present and members of the general public.

In this simple and gleeful way, the inhabitants of Busturialdea would celebrate the festive morning and afternoon of the feast-day. These days of celebration, with their dances, opened up the way for possible courtships and good relations with neighboring youths of different communities (although, on occasion, some rivalries would occur), the youth associations' relations with local authorities of personalities (be they local or regional). They also helped to fulfill a social role for youth (since they would act as a sort of organizing committee for the celebrations, and as representatives of the collective at these festivities).

At the same time, one of the functions of these youth associations was the socialization of their members. During the age cycle, and referent to sexual gender, the future function of the youths within the center of rural society was progressively configured. The lads were prepared for their active participation in family life, as well as for their community's social and work activities. Meanhwhile, the girls were also instructed for their future responsibilities relating to tasks of the "etxeko andre" at home, teaching and bringing up children, as well as the conservation of domestic religious functions.

The group of young men is manifestly social, since it organized festivities and controlled possible divergences while being watched and evaluated by adults, and latently allows for them to make the passage to the category of married men, by serving to create relationships between members of both genders, as well as marriages, something necessary for the social group, inasmuch as fertile marriages are concerned.

It also served as an age group that is entrusted with social control, and with safeguarding the spatial limits of the social group. These groups of young men established relations as neighbors or rivals with other nearby bachelors' groups, as well as establishing cordial relationships with local authorities or village VIPs.

The end results give us an idea of the characteristics, organizational systems, rules, and surroundings of the bachelor associations described in this report.

Definitively, "traditional" societies, owing to their economic and social structure, have conserved some rather rigid, stable, or cultural elements that are slow to change. Rural or farming cultures in Europe, while they try to avoid being both idealized and undervalued, shows themselves to be the custodians of a life system or lifestyle evocative of past eras, but with a concrete sense or meaning for each collective, at different historic or social moments. Their richness and diversity confirm the fact that the ways of life and beliefs of traditional communities (just as in any other society) are dynamic, and, are therefore susceptible to evolution, transformation, and even disappearance.