The Alboka

- Ibon KOTERON

- 15/ 10/ 2001

I would like to particularly thank Manu Gojenola and my brother, Aitor Coteron, for the photographs.

Sections:

1. GETTING TO KNOW THE INSTRUMENT

1.1 Parts of the alboka

1.2 How to hold the instrument

1.3 Producing the sound

1.4 Size and parts of the alboka

1.5 Range/key of the alboka.

2.THE ALBOKA TRADITION

2.1 Albokaris ("albokariak" or "albokeroak")

2.2 Related instruments

2.3 Traditional music for the alboka

2.4 The alboka today

3. BASIC DISCOGRAPHY

4. SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. GETTING TO KNOW THE INSTRUMENT

1.1 Parts of the alboka

Although a first glance, it may seem the most noticeable feature, the alboka (or albokea, as León Bilbao always called it-we've never heard anyone say albokak) is not a "horn", at least not inasmuch as its sound production is concerned. The sound is produced by two small double reeds (see photos), and not by labial vibration, as it is in hunting and signal horns, trumpets, trombones, and other instruments of that family.

However, it is true that the etymological root of its name is found in al-bûq, and this word itself does, indeed, mean "horn", and I understand it to be the generic equivalent of the Anglo-Saxon term horn. A very approproate term would be hornpipe (note 1). Friends of mine from Navarre, who have come to know the instrument through me, call me "el cuernico" (lit. "little horn").

Apart from the "little horn" (or, for alboka players, "big horn", or adar aundie), there is another one which really is (small, that is)-the adar txikie, substituted in some cases by a flared wooden piece housing the fitek, traditionally two small reeds that, as mention above, serve as mouthpieces.

TRADITIONAL FITAS IN THE ADAR TXIKIE.

TRADITIONAL FITAS IN THE ADAR TXIKIE.

ALBOKA WITH WOODEN MOUTHPIECEBUILT BY "MUNDI" FLORES, SANTURTZI.

ALBOKA WITH WOODEN MOUTHPIECEBUILT BY "MUNDI" FLORES, SANTURTZI.

Over these closed cylindrical reeds, on one end, (formerly by the actual knot of the reed, now a plug does the job), a length-wise partial cut is made from the closed en towards the open end, in such a way that it creates a double reed effect, and it vibrates over the rest, which serves as a base

FITAS WITH RUBBER STOPPER BUILT BYJUAN ANTONIO MARTINEZ OSES, OTAZU.

FITAS WITH RUBBER STOPPER BUILT BYJUAN ANTONIO MARTINEZ OSES, OTAZU.

SHOOT WHERE THE CUT IS MADERESPECTING THE KNOT AT THE END.

SHOOT WHERE THE CUT IS MADERESPECTING THE KNOT AT THE END.

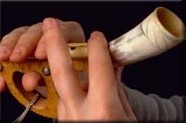

TRADITIONALLY METHOD USED FOR BUILDING FITAS

SLIGHTLY SLOPING INCISION.

TWIST OF THE WRIST TO RAISE A SHEET.

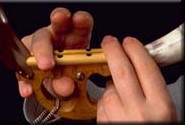

TWIST OF THE WRIST TO RAISE A SHEET.

RAISING IT.

RAISING IT.

LENGTHENING TO THE REQUIREDMEASUREMENT.

LENGTHENING TO THE REQUIREDMEASUREMENT.

A bristle (note 2) introduced into the slot impedes the reed from sticking to the base, and stops the fita from "choking". Next to it, a ring made of thread is used for tuning adjustments, shortening or lengthening the vibrating portion of the reed.

Currently, standard bases are manufactured in plastic or wood, with separate reeds, such as those for clarinet, although smaller. In fact, single-reed instruments are known generically as "clarinetes".

FITAS WITH WOODEN BASE BUILTBY JOSEBA GAZTIAIN, ANTZUOLA.

FITAS WITH PLASTIC BASE BUILTBY JUAN ANTONIO MARTÍNEZ OSES.

FITAS WITH PLASTIC BASE BUILTBY JUAN ANTONIO MARTÍNEZ OSES.

The sound produced by the fitek is transmitted to, and in turn modulated by two narrow cylindrical pipes (traditionally made of reed, or a pipe handily supplied by nature (note 3), but now made of turned wood, with three and five holes, respectively, the first alligned in pairs from the open end of the pipe towards its bell. The large horn (note 4) makes a resonating chamber, and may or may not be fixed to the wooden yoke (bustarrie) that joins the set together.

1.2 How to Hold the Instrument

We can see that all albokas are made for right-handed people: for the positions of León and Txilibrin to be the same, the latter's alboka would have to have a pipe with five holes to the right of the other (note 5).

A TRICK OF THE EYE, NEITHER DID LEON DID PLAYIN THIS POSITION NOR DID HIS ALBOKAS HAVE HOLES THERE.

A TRICK OF THE EYE, NEITHER DID LEON DID PLAYIN THIS POSITION NOR DID HIS ALBOKAS HAVE HOLES THERE.

Not all yokes are equally comfortable, and this depends in an inverse manner on the complexity of their design. Using a right-handed person as a reference: the right thumb must be in vertical with respect to the middle finger, and as close as possible to it, and this means that the yoke must have a conveniently situated hole, as well as another in which to introduce the little and ring fingers of the left hand, which press the alboka against the albokari's face. The left thumb must lean against the small horn, either at the end, or where it joins the yoke.

The right little finger used to hold the bell when it was loose, but this position is uncomfortable, and when the finger sticks up in the air, the effect is not aesthetically pleasing. It is better to point it down or to lean it against the yoke, nearby the bell itself.

ALBOKA BUILT BY TXILIBRIN.

ALBOKA BUILT BY TXILIBRIN.

ALBOKA BUILT BY IMANOL ATXA GOITIA, BILBAO

ALBOKA BUILT BY IMANOL ATXA GOITIA, BILBAO

1.3 Producing the Sound

1.3.1 Getting Ready to Blow

One needs to apply a certain amount of pressure so that the air cannot escape between one's face and the adar txiki. The closed ends of the fitek must be supported just under the lips, and the player must not open his/her mouth very much. When beginning to blow, the player's tongue pulls back from the inner surface of the incisors, similarly to the way we do upon pronouncing the letter "t", but without the sound produced by the vocal chords-only with the breath. In other words, with what some erroneously call a "stoke of the tongue" (erroneous because what the tongue actually does is to move away, not strike). Only in this way will the player be able to begin to blow firmly.

1.3.2 Circular Breathing or Continuous Airflow

a) What are we talking about?

It is known that playing the alboka means having to blow continuously (although I have come across people who equivocally thought that the sound was obtained as in a harmonica: blowing and inhaling alternatively).

Although the technical term is "continuous insufflation", a more common term would be "breathing", which actually makes sense, since in order to blow, one must breathe. In this case, the player must do it bit by bit, without ever stopping blowing, according to an old technique that is not at all exclusive to the alboka. (The late Pío Lindegaard asked me once if this was a traditional technique, or if the albokaris had copied it from jazz musicians.) It is a widely-used technique for many traditional wind instruments, as well as in the craft of glass-blowing.

b) Getting rid of preconceived ideas: This technique is not difficult.

Contrary to what has always been said about it, such a widely used and supposedly ancient technique as this aims to eliminate difficulties, not to increase them. In fact, we can say that once this technique has been learnt, playing the alboka isn't more tiring than playing other standard woodwind instruments; it is probably less tiring. The myth that the difficulty in playing the alboka lie in the breathing techniques have been promulgated by the very albokaris, in order to inflate their own importance, and by many folklore fans wanting to point out the "special" qualities of this instrument but it hasn't helped the alboka-to the contrary.

But not only what has been said (note 6), but what albokaris have contributed to exaggerating the issue: the traditional teaching system consisted of blowing bubbles through a reed in a glass or soapy water, and no more fancier method than that. As we can see, this method has the advantage that, even when the teacher cannott think of any other way to explain things, pupils can continue to learn on their own (an unintentional application of operative conditioning), and it also has the disadvantage that many will give up, which helps continue to confirm the idea that it is difficult.

We must clearly say: it is not difficult, nor is it the easiest thing about the alboka.

1.4 Size and Parts of the Alboka (note 7)

Traditional albokas are made "by sight", using available materials. The interior diameter of the pipes themselves is where most variation occurs (from 6 to 8 mm., 7 mm. being the current standard) and, as a result, the diameter of the fitas varies as well. The acoustic phenomenon itself is largely important in this sense, because the narrower the pipe, such as is the case of the alboka, the more restrictions it imposes on the source of sound: the length of the fita, and especially the reed must be proportionate to the pipe, for to the contrary, it will not produce a good sound. This length (from 130 to 166 mm.) would have depended on the size of the hands of the albokari by whom or for whom the alboka was made. Holes (with a diameter from 3.5 to 5.5 mm.) were equidistant, and placed where the fingers would fall naturally, and the total length of the pipe always kept the same proportion regarding the distance between the holes on either end (note 8).

1.5 Scale/Range of the Alboka

1.5.1 Starting Point

There has been much talk about this, although not very well substantiated. The instrument's acoustic base is as follows: the sound emitted y the mouthpiece depends greatly on its vibration, and the latter is subject to change according to the resonating pipe (down to the end of it, or to a little bit further than a point of interruption along it, such as that created by an open hole). As indicated earlier, the narrow pipes of the alboka dictate the dimensions of the mouthpiece.

These differences in length mean, therefore, that the longer the pipe, the lower the scale. If we take into account the above observations, it would not be difficult to make albokas "a priori", in all the different sizes as documented in fieldwork, and to be able to come to a conclusion as to whether or not many of these ranges really existed, or if they are results of researchers' methodological mistakes or, if upon using inadequate fitas in taking their measurements, or if tuning had not been adjusted. There exist reasons to be certain of this in some cases; in order to understand them, we must look at:

a) a. What we Know from the Past:

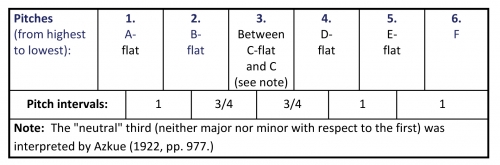

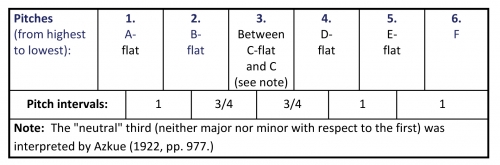

The intervals of León Bilbao's traditional alboka (without making a distinction between major and minor keys) would have been as follows:

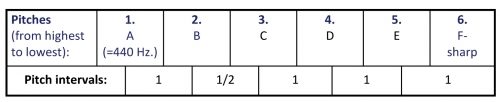

On the other hand, Txilibrin's range would be:

Thanks to a proposal by J. M. Barrenetxea and P. J. Riezu (1976), as well as to modern makers such as Juan Antonio Martínez. Osses (Otazu) and Joseba Gastiain (Antzuola) among others, today's albokas sound one half-tone higher, and not all holes are equidistant, in such a way that the instrument now approaches a standard "tempered" scale.

The regularization of intervals was indispensable in order for the instrument to be able to play with other (non-percussion) instruments, although another option would have been to begin the scale with G instead of with A (note 9). It is, however, this half-tone difference in pitch that distinguishes the timbre of today's alboka from those of before, since it has a less brilliant but rounder sound.

b) Fingering for the Alboka:

Classification:

We have already explained how to hold the instrument, but how does the player cover and uncover the holes in order to produce sounds? Let's look at it diagramatically (or, for right-handed players, in a mirror, lifting your fingers exaggeratedly, in order to see more clearly):

Basic or Closed Fingering (León Bilbao):

LEFT PIPE "A - A" RIGHT PIPE

LEFT PIPE "A - A" RIGHT PIPE

LEFT PIPE "B - B" RIGHT PIPE

LEFT PIPE "B - B" RIGHT PIPE

LEFT PIPE "C - C" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "C - C" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "D - D" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "D - D" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "E - A" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "E - A" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "F# - A" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "F# - A" RIGHT PIPE.

In each position, only one finger will be lifted: "closed fingering": continues to be so even a finger on each hand has been lifted, because only one sound corresponds to each movement upon uncovering holes on different pipes (such as in ornamentation and double-stops, which we will look at further ahead). Note in the notation that the A in parentheses is not indispensable.

Fingering stops being "closed" when more than one finger of the same hand is lifted at the same time. Then, it becomes:

1) Open: When the player uncovers all the holes on a given pipe (or those notes played by one hand) between the note sounding and the end of the pipe. Some albokaris use this system more or less often for reasons of comfort. For example, Txilibrin:

"C - C"

"C - C"

"D - D" (ASCENDING ONLY)

"D - D" (ASCENDING ONLY)

2) Semi-open or semi-closed: Fingers on the same hand (same pipe) are lifted. Usually, while one note is sounding, the position for the next is prepared. León Bilbao played as follows:

"D" FOLLOWED BY B.

"D" FOLLOWED BY B.

"D" FOLLOWED BY C.

"D" FOLLOWED BY C.

"F" FOLLOWED BY "E"

"F" FOLLOWED BY "E"

Application: As we can see, the general rule is that of minimum effort. For this reason, there are two types of musical devices for the alboka that use this "semi-open" fingering:

1. Trills, half-trills, and more or less quick rolls made up of two "notes" (whether or not they are adjoining intervals on the scale), as long as one of them cannot be produced on the left pipe, and the other may be produced on both.

2. Mordents or very quick grace notes. When the mordent is done with the left pipe and the other note is not, both are simultaneous (and the fingering is closed). In all other cases, they are played in extremely rapid succession (and the fingering is semi-closed).

From this stems the idea that the left tube is not just "melodic", and the right is a "pedal" or a "redoubling" with low notes (Barrenetxea & Riezu, 1976). Many times the melody is played with the right hand, while the left plays pertinent ornamentation and mordents (always descending in the traditional repertory), which have three functions: duplicating a note that would otherwise have been continuous; accentuating certain notes; and marking a rhythmic sequence). Double-stops may be played in which either one of the hands may take the main "voice". Positions for each of these cases are as follows:

Basic Fingering: Simultaneous mordents and double-stops.

Note: (We will not indicate positions for successive mordents: any of the fingers of the same hand may be lifted at the same time and only the one to which the mordent corresponds is put back down very quickly. In traditional alboka repertory, mordents are always descending. Also, two fingers of one hand remain lifted for an instant when trills and semi-trills are played.

LEFT PIPE "E - B" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "E - B" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "E - C" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "E - C" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "E - D" RIGHT PIPE(ONLY MORDENTS ).

LEFT PIPE "E - D" RIGHT PIPE(ONLY MORDENTS ).

LEFT PIPE "F# - B" RIGHT PIPE

LEFT PIPE "F# - B" RIGHT PIPE

LEFT PIPE "F# - C" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "F# - C" RIGHT PIPE.

LEFT PIPE "F# - D" RIGHT PIPE

LEFT PIPE "F# - D" RIGHT PIPE

As we can see, some of the possible combinations have not been used except for mordents. It is logical that an E/D double-stop is not held for too long, since it is a dissonance. There are other possible combinations, if, with the right hand we do not obstruct both tubes at the same time, although we will not be covering them in this work.

1.5.2 A Refresher about the Scale.

There is one necessary conclusion: except in a few cases of double-stops, the 5th and 6th steps of the scale are always accompanied by the 1st. However, the interval between the 1st and the 5th steps is a perfect fifth (see 3/2) in the live example of a traditional alboka (as seen perfectly in the case of León Bilbao). But the consonance of this interval is a universal phenomenon of the human ear, and we do not believe that this interval, if out-of-tune, sounded good to albokaris or to their public. It would be preferable to have to un-tune the unisons (Txilibrin, in many cases), independently of the slight variations that may occur in the other notes along the scale. (note 10)

In principle, it would be possible to reconstruct scales of albokas having pipes of varying lengths (although we had not ever seen or heard them before), by drilling holes according to the mathematical proportions we have discovered (see note 8 of pararaph 1.4), and also by using fitas that respect the interval of 5th between the first and fifth steps of the scale.

2. TRADITION OF THE ALBOKA

2.1 Albokaris ("albokariak" or "albokeroak")

Today's knowledge of the alboka has comes to us from two sources: a still thriving (although certainly atypical) tradition, and also through the information brought to us by folklorists and other scholars (see bibliography).

By 1918, Resurrección María de AZKUE, in conferences subsequently published in her "Cancionero Popular Vasco" (Collection of Basque Popular Song), lamented the fact that "there are only a few albokari left" (trans. Note: albokari> players of the alboka). It is more likely, however, that there never were very many in the first place. In any case, the most complete reference to the albokaris of this and last century is that of Barrenetxea, which lists the names and surnames of notable 34 albokaris (1976, p. 106), as well as three others as transmitters of the instrument's repertory (p. 107). It also mentions pieces of information about another four who remained anonymous. Missing from the list are Juan Lekue, originally from Dima but residing in Deusto, who died not many years ago, and Juan Otxandio, from Usansolota, living in Larrabetzu, who passed away near the end of 2000.

According to these lists, the alboka's scope included the area immediately surrounding the massif of Gorbea, Azkorri (note 11) and the Urbasa mountains, very ancient pastoral lands. Qualifying the alboka as a "shepherd's instrument" is a typical cliché that should be examined. According to Baines (1960), according to its geographical distribution over the entire old continent, the origins of this type of instrument were in the nomadic livestock-herding societies of the Neolithic, or "shepherd" societies. But this is far from saying that all of those who played the albokara were shepherds. León Bilbao stated: "Shepherds? Why not just not even talk to the shepherds?" There have been albokaris who were shepherds, but many were baserritarras. Even Juan Otxandio and Juan Lekue, according to the latter, as boys, took the sheep to the mountain every day: they were shepherds, then, but not in the sense in which this term is usually used, associated with long journeys or farming shelters, and even migrations. It would seem to us, then, that is would be more correct to say that the traditional environment of the alboka is rural, but not "pastoral".

2.2 Related Instruments

There are many double-clarinets throughout the old continent, but I have only found one similar to the alboka, with five holes on one pipe, and three on the other (or, really five as well, but stopped up with wax), although it had a bag attached, which gives it its name in some places: in Turkey tulum; in Greece aski. In Adhzaria, it is called chiboni or chiponi, and stiviri in Georgia.

Although its scale is practically the same as that of the alboka (see below) Dr. Baines himself (1960, p. 45) indicated its musical forms were completely different.

In the Iberian peninsula, the alboka has no close relative. The Bagpipe found in the mountains of Madrid has only one pipe and four (sometime five) holes: The Xeremia of Eivissa has an equal number of holes (five) on both pipes. Neither is its range the same, nor is played with a continuous sound or breath.

What about the "albogue"? Azkue used "albogue" as the translation of "alboka". Since then, manyh have described it as a portrait of our alboka, but there is no basis for this in Castilian literature: in El Quijote, it is a sort of cymbal, in other contexts, there appears a more or less generic term for "bagpipe" or "chirimía". (See Diccionario de instrumentos musicales [Dictionary of Musical Instruments] by Ramón Andrés: Barcelona, Vox, 1995.)

Several authors (not including P. Jorge de Riezu) have taken as certain several things:

1. That the etymologies of "alboka" and "albogue" are the same (from the Arabic al bûq); and

That, therefore

2. They must be the same instrument.

When Aranzadi as well as Barrenetxea put forth arguments against it, (1) it is because they don't believe, even making this supposition as a premise (2) that a derivation necessarily took place, although we think that it is unsustainable, (2) while on the other hand, it may be that (1) there is no logical connection between either of these theories.

2.3 Traditional Alboka Music

2.3.1 Sources

Despite the more or less long lists of traditional albokaris, we have never met one that played as well as León or Txilibrin. The only recording I have ever heard of a player that even came close in ability was one of an anonymous albokari, made by Alan Lomax in 1952 (see note 12). Even so, this recording seems to confirm what León Bilbao said: each albokari played a couple of melodies, and no more. Our sources include:

1. León and Txilibrin's repertory, where more or less everything there is to collect has been collected. They have a number of recordings ranging from the commercial to the rustic.

2. The repertory of albokaris from Guipuzkoaperhaps with a freer form, not as adapted to competition with romerías with accordionists and shawm-players.

3. The transcripts of Barrenetxea & Riezu (1976), much of the preceding (and more) may be found.

4. A few alboka melodies compiled by Azkue in Cancionero popular vasco (Book of Basque Popular Song) (1922).

5. Adaptations for accordion-trikiti(x)a-, especially by Fasio Arandia.

However, unfortunately, we were not able to get recordings of other albokaris (including some as famous as José María Bilbao and Antonio Aiesta "Gitano"), although they exist among materials in the Basque film archive-I believe- and, fundamentally, in the body of work recorded by J. Mariano Barrenetxea, whose publication on behalf of some institution would prove indispensable, especially considering the fact that transcripts can be infinitely inferior to recordings.

2.3.2 Characteristics

a) Rhythms

Apart from some sui generis songs and melodies, most traditional pieces can be placed in one of three rhythmic categories:

1. Tertiary: especially "jotas" (A = 8 repeated bars, B = 8 repeated bars, C = 28 bars accompanied by singing or with a 7-point verse), as well as some fandangos (with parts lasting 8, 16 or 32 bars).

2. Binary: especially "porrusaldas" (A = 8 repeated bars, B = 8 repeated bars, C = 20 bars accompanied by singing or with a 5-point verse).

3. Binary with a tertiary subdivision: "martxa", "kalejira" or "biribilketa".

b) Tonalities

The traditional repertory constantly uses the note given by the alboka with ll holes covered as the tonic, and the 5th as the dominant. In the present-day alboka, the Doric mode is used, or a kay of Am with an augmented 6th. However, we have seen how scales such as that of Txilibrin, with its neutral third, might sound like a major key to the academic ear-G major in the case of Azkue (1922, p. 364).

c) Style

Playing style for the alboka is a consequence of its continuous sound, and the fact that is has a double pipe. It cannot be played "without ornamentation" (this will be systematically dealt with later), because it is in the ornamentation (mordents, semi-trills, double-stops, and notes made staccato through different fingerings-the only way to create this effect) where much of the life of the melodies lie: separation of notes, their rhythmic content, use of polyphony... All of which are truly necessary resources when dealing with an instrument of such limited range (not even an octave), and on which "you can't just play anything". But one can play more than what was being played up until recently.

2.4 The Alboka Today

Let us look at today's alboka within the traditional framework: after a period of some uncertainty, the instrument has become relatively popular once again, and traditional style has been abundantly maintained, although its polyphonic possibilities have been developed, and new types of ornamentation and more complex fingerings have been added (including half-holing, and alternating pipes...) The repertory is being considerably but coherently extended by means of new, traditionally structured (or not) compositions, based on Basque melodies and those of other countries (see note 13), and by playing pieces in varying keys... Even Txilibrin, in the space of only a few years, has gone from saying, "that's not for the alboka" to stating his discontentment for "what everybody played before: always the same old thing. What we have to do is play songz [sic] from Euskal Herria". Someone once asked León Bilbao if the budding albokaris were good or bad. We hope he was right when he replied, "They'll be better".

3. BASIC DISCOGRAPHY

1. The Best Recordings of Traditional Alboka Music:

León Bilbao:

ARRATIA (1975): Arratia. Herri musika sorta, XV. Edigsa.

KARDANTXA (1977). Movieplay.

Bai euskarari (1978). Recording of the festival.

LEON, MAURIZIA, FASIO (1979): Alboka eta trikitixa. Bilbao: Xoxoa. Also, later (1998) on CD, together with LEON... (1988). Other recordings from the 1979 session appear in a reissue from Madrid.

BELTRAN, Joan Mari (ed.) (1985): Euskal Herriko Soinu tresnak. Donostia: IZ. Also later in CD. Other recordings included in a fundamental video under the same title.

LEON, MAURIZIA ETA BASILIO (1988). Donostia: Elkar. Also later (1998) on CD, together with LEON... (1979).

Silvestre Elezkano "Txilibrin":

GARCÍA MATOS (1978): Magna antología del folklore musical de España. (Great Anthology of the Folk Music of Spain) Madrid: Hispavox. CD edition: 1992. This recording is from the 1950s.

ANTOLOGÍA DE INSTRUMENTOS VASCOS (1971). Columbia, CPS 9133.

TXILIBRIN ETA BALBINO (1975, 1988): Trikititxa (Sic). Madrid: Columbia. Reissued by BMG Ariola.

NUKLEARRA? EZ, ESKERRIK ASKO (1980). Recording of the "Herrikoi topaketak" festival. Donostia: IZ.

Mikel URBELTZ (1995) Berrizko itsuari. Donostia: Ikerfolk-Elkar. Fundamentally repertory of Barrenetxea & Riezu (1976), played on the violin. Txilibrin and Daniel Lara on the alboka.

GORBEIALDEA: Dantzan. Galdakao: Bolingozo. (Video.)

La tradición musical en España: I: La cornisa cantábrica. XIV (Traditional Music in Spain, part I: The Cantabrian Shelf. XIV): Instrumentos tradicionales (Traditional Instruments). Madrid: Saga.

Anonymous Alboka Players:

LOMAX, Alan (ed.): Spanish Folk Music, in The Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music, vol. XIV. This recording is from August of 1952, edition unknown. The second porrusalda is magnificent, but only the name of the pandereta player is known: Arantza Goichi (sic). Anonymity, however, does not detract from the performance of another albokari who plays in the first piece, and who is included under the next heading.

2. The Decadent Phase of the Alboka:

BARRENETXEA, J.M., ZULOAGA, Romualda & ARRIETA, Marcelo (1964): Alboka. Bailables vascos (The Alboka: Basque Dances). Bilbao: CINSA.

DANTZAK (1978): Herri musika sorta, I. Donostia: Ots. Anonymous Albokari.

3. Today's Alboka Recovered:

Together with attempts (some should be included in under the previous heading) by AZALA, LAUBURU, IZUKAITZ, EXKIXU... the alboka truly revives the work of OSKORRI , TXANBELA, KEPA JUNKERA, TOMÁS SAN MIGUEL... Some of the most outstanding are:

IBON KOTERON & KEPA JUNKERA (1996): Leonen orroak. Donostia: Elkar.

ALBOKA (1998): Bi beso lur. Hernani: Aztarna. Wonderful Alan Griffin on the alboka.

JOXAN GOIKOETXEA & JUAN MARI BELTRAN: Beti ttun-ttun. Orereta-Rentería: NO-CD.

GASTEIZKO FOLKLORE ESKOLA: Música autóctona vasca. (Autoctonous Basque Music) Karlos Subijana on the Alboka.

4. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANDRÉS, Ramón (1995): Diccionario de instrumentos musicales (A Dictionary of Musical Instruments) Barcelona: Vox.

ARANZADI, Telesforo de (1916?): "Alboka y Albogues", (Alboka and Albogues), from Euskal Herria, pp. 152-158.

AZKUE, Resurrección María (1922-3): Cancionero popular vasco (A Book of Basque Popular Song). Edición Manual. Quotes from the new Euskaltzaindia edition, Bilbao 1990.

BAINES, Anthony (1960): Bagpipes. Oxford: Pitt Rivers Museum. Citamos por la 3ª edición: 1995.

BARRENETXEA, José Mariano & RIEZU, P. Jorge de (1976): Alboka. Entorno folklórico (The Alboka: Surrounding Folklore). Lekaroz:. Donostia public archives.

BARRENETXEA, José Mariano (1983): La alboka (The Alboka). Separata by Eusko Ikaskuntza.

BARRENETXEA, José Mariano (1986): La alboka y su música popular vasca (The Alboka and Popular Basque Music). Author's edition.

BELTRÁN, Joan Mari (1996): Soinutresnak Euskal Herri musikan. Orain.

BIKANDI, Sabin & SANTAMARÍA, Jabi (1997): Uztarri. Alboka doinuen bilduma. Gasteizko Udala.

LOPEZ DE ELORRIAGA, Jose Maria (1969): "A alboka". Two articles in the Boletín Sociedad Excursionista Manuel Iradier, n. 102 ( pp. 33-44) and 104-105 (pp. 22-29). Vitoria

GARCÍA MATOS, Manuel (1956): "Instrumentos musicales folklóricos de España" (Folk Instruments of Spain), in Anuario Musical (Annual Musical Digest), Barcelona, pp. 123-163.

LARREA Y RECALDE, Jesús de (1930): "La alboka" (The Alboka), in Euskalerriaren alde, #20, Donostia.

VARELA DE VEGA, Juan Bautista (198?): "Anotaciones históricas sobre el albogue" (Historical Notes on the Alboka), in Revista de folklore (Folklore Magazine), Valladolid, pp. 21-27.

(1) In fact, according to BAINES (1960) the alboka is the only instrument of this type that, having a yoke or support for its other parts, does not have a bag (in other words, it is not a bagpipe). See Diccionario de instrumentos musicales, (A Dictionary of Musical Instruments) by Ramón Andrés: Barcelona, Vox, 1995.

(2) León Bilbao used hair from his own chest, which can only to joke about the fact that there are those who said that the alboka is an instrument of Arab origins because it was made using the "hair of a lion". Despite this myth, it is true that horsehair is too think, and lifts the reed too far. It lets air escape and no matter how one blows, no sound is produced. Personally, I prefer nylon thread.

(3) There are known instruments made out of a stork's leg.

(4) If the animal is too old, the point of the horn solidifies, and it needs to be hollow: According to León Bilbao, it should be the horn of a cow from three to six years old.

(5) The alboka photographed by BAINES (1960, illustration #12, sheet IV) seems to be an example of this, since its pipes are changed around, which would be logical if it had been made for or by a left-handed albokari. This, then, would not be owing to an "assembly error", as suggested by J. Mariano Barrenetxea (1976, p. 5, #6). But, as it turns out, it was neither one nor the other: when the book was printed, the plate was positioned in reverse. Demonstration: on page 49, figure 26 of BAINES's book, there is a diagram of that alboka, and its pipes are arranged in the same way as those of any other. This is also indicated in the text.

(6) "Breathing" is the topic of the famous story about the albokari who played all day long on the longest street in Paris, on muleback or horseback, in order to win a bet, mentioned by Azkue (1922). This story appears in verses from the traditional alboka repertory.

(7) Fundamental data may be found in BARRENETXEA J.M. & RIEZU, P.J. (1976, p.15)

(8) Among the sixty-odd albokas studied by Barrenetxea (1976, p.15), the longest of their pipes measured 166 cm, and the holes on either end were 106 cm apart. This distance was reduced to 83 cm. for pipes measuring 130 cm long. In both cases, the proportion was 1, 566. What an amazing coincidence!

(9) The albokari recorded by Alan Lomax in 1952 started his scale on a somewhat flat G (see The Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music). There also exists a re-issue of this recording by Rounder (1999), but I don't know if the recording is good or not. I do know that there is a frankly bad recording by another albokari, whose range began with A-flat. For more information on the controversies surrounding the scale of the alboka, please visit my previously mentioned web-page.

(10) It is also recommended to check the alboka's tuning (tuning diagnostic).

(11) Could it be that the albokari from Guipuzkoa learnt from the people of Arratia, as Azkue (1922, p. 258, note) says one from Idiazabal told him?

(12) The scale of the albokari recorded by Alan Lomax in 1952 and issued in the Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music, begins on a somewhat flat G. There has been a reissue by Rounder (1999), but I don't know if this recording is good. I know that there is one of a frankly bad player whose range began on A-flat. For more information on the controversy surrounding the scale of the alboka, please visit my previously mentioned web-page.

(13) Something that albokaris have always done: see Azkue (1922, p. 257) how one tried to play "la gallegada", (t.n.: Galician-style), but didn't have enough range. (Let us say in passing that the low F# from that transcript must be a G, because the alboka doesn't actually give seven notes.)