Bizkaiko Dultzaina

- Jabi Santamaría

- 15/ 10/ 2001

What we call the Bizkaiko dultzaina, or dulziņa is a wood instrument with a double reed, a length of about forty centimetres including the mouthpiece and which has been traditionally played in Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa. Aside from the dulzaina, other instruments with a double reed are played in the Basque Country: the pipe, played in Araba and Nafarroa (thus called alavesa or navarra), and the Txanbela, which they used to play in Zuberoa.

Sections:

The instrument

The social context

The men

The decline of the dulzaina in the 20th century

The current situation and future perspectives

The instrument

The dulzaina is made up of two different parts: the pipe and the mouthpiece.

The dulzaina

The dulzaina

The pipe

The mouthpiece is conical, is 330 mm long on average, has six holes on the top (although some of the dulzainas made by Jose Sudupe "Montte", from Azkoitia, have seven, like the Navarre pipe) and one hole under them.

There are an additional two, larger, holes near the lower part. These are called aires. The pipe is generally made of brass, sometimes with no finish (which gives us the reddish dulzaina) and others, with chrome plating, nickel plating or silver plating (called silver dulzainas).

The dulzaina has also been made of other materials (Jose Sudupe "Montte", from Azkoitia, made them of stainless steel and wood), but those made of steel had a more imperfect finish due to the lesser malleability of stainless steel in comparison to that of brass. Although some folklorists believe that prior to the dulzainas made of metal there were wooden dulzainas in Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa, it should be noted that all traditional dulzaina players in Vizcaya in the 19th century have played with metallic dulzainas; even those who owned a wooden dulzaina had purchased it or brought it from the Estella area in Navarre, the origin of famed pipe players.

The mouthpiece

The mouthpiece is the most important part of the dulzaina as this is where the sound, which is later modulated and amplified in the pipe, is produced. The mouthpiece includes two parts: the tudel (or taudel, as it is called by the dulzaina players of Orduņa), is a metallic piece about 4-5 centimetres long and conical in shape. Its widest part joins the pipe and the narrowest section, which is somewhat flattened, is tied to the "fita", or pita, the second part of the mouthpiece.

The fita is the double reed, i.e., the part that vibrates. It is usually made of reed, although there are references to other materials such as willow or hazel wood, bird bone and animal horn.

A carpenter from Basatxu (Cruces-Vizcaya) even came up with a very original variation: he made the entire mouthpiece of reed and in one single piece (tudel plus fita).

Photograph of a traditional mouthpiece, tied with hilobala

Photograph of a traditional mouthpiece, tied with hilobala

The tuning

The Vizcayan dulzaina is normally tuned in Do flat (located between Do natural and Do sharp), although some are currently being built with the tuning in Do natural, which makes it easier for them to form part of musical groups.

The fingering of the dulzaina is similar to that of a recorder in its natural sounds:

As for the changes, though the method of the tranquilla can be used (opening the hole of the note which is higher than the one you are trying to produce while closing the one which comes immediately before it), it is also necessary to modify pressure on the mouthpiece to reinforce the effect.

You can even obtaining the changes by working only with the modulation of the mouthpiece. However, this requires a extensive training of the ear and great mastery of the mouthpiece by the person who does so.

It is important to note that traditional dulzaina players have always played in 'simple' tones with little or no changes (DoM, SolM, FaM, Lam, in on rare occasions, Dom). With regards to the range of the dulzaina, we could say that it is divided into two parts. The first goes from Sol4 to Sol5, which are produced by covering consecutive holes, while the second goes from La5 to Do6. To obtain these notes you must increase the air pressure on the mouthpiece in order to produce, with the same position, the jump in ocatave.

This division has been given different names by the Vizcayan dulzaina players: playing "high" or "low", or "thins" and "thicks" (due to the volume in each area). It has also become a way of distinguishing the ability of the players, as you can hear comments such as: "He was an incomplete dulzaina player, he could only play the low notes." Players who knew how to play "the highs" kept the secret of this technique under lock and key.

The social context

A little background history

The first written evidence of the dulzaina is recent. In 1741, we can find a payment to Manuel de Bustrin "for his salary as a tanbolitero and dulzana" in the locality of Arretxinaga (Vizcaya).

Prior to this there are other references, but they are made with the name gaita, or pipe, as the double-reed instrument is known in Navarre and Alava. We are thus left in doubt as to whether it refers to the dulzaina or to another type of instrument - one must keep in mind that the name gaita has been and is used, depending on the region of Spain, to describe double-reed instruments with or without bellows, flutes, albogues or zanfoņas. It is even likely that the introduction of the term "dulzaina" was created through a wish or need to set the instrument apart from others which were given the general name gaita.

The fact that there is little written reference of the dulzaina is logical; it is the result of the social role played by this instrument.

The dulzaina was not an official instrument of the Consistories. When they needed to hire musicians in Vizcaya, they hired drummers (now called txistularis) as can be seen in numerous documents of payment. During pilgrimages, the pilgrims themselves paid the musicians as we will see further on, but no written evidence of this remains.

The skill of the local dulzaina players must have been considered insufficient if you take the following facts into account:

- In 1828 the King of Spain and his wife, Fernando VII and Amalia de Sajona, arrived Durango. For the festivities that took place, a group of dulzaina players were brought in from Guipúzcoa.

- During the Fiestas Euskaras of Guernika in 1888, the prize for the best dulzaina player was not awarded. It included the participation of "a dulzaina player from Aulestia but he was not considered worthy of the prize."

The dulzaina player and his accompanists

In spite of our constant mention of the dulzaina player, one cannot forget that the dulzaina has been accompanied by other instruments and players who we set out below:

- Dulzaina player (dultzaineroa): Always in singular. At times two people have played the dulzaina, but taking turns. Although they knew how to play a duet they rarely did so because of the understanding required between them and the tuning of instruments and fitas.

- Drummer (danborreroa): Accompanist of the dulzaina player. Along with him, he comprises the minimum group of musicians.

- Tambourine player (panderujolea): We have references of the fact that, at times, the dulzaina player was accompanied by one or more tambourines, although they were generally musicians who began following him during the pilgrimage.

- Bertsolaria: Both the jota and the porrusalda (pilgrimage dances which survive to this day) included a part called "Kopla" , named thus because some verses with the structure of a Spanish folk song (copla) were sung. These verses, although generally sung by the panderujole, were sometimes performed by others who, in the style of the bertsolaris, improvised these "coplillas" for the situation at hand.

- Accordionist (trikitilaria): A dulzaina player appears alongside a trikitilari in some illustrations and photographs. Given the differences in the tuning of these instruments, this did not happen often; they were more frequently competitors during the pilgrimages.

- Collector (kobradorea): A fundamental figure around the popular musicians and pilgrimages who was in charge of collecting money from the couples who were dancing. The amount, charged for each dance, was a "txakur txiki", or five centimo coin at first, eventually rising to a "txakur haundi", or ten centimo coin.

The pilgrimages

A pilgrimage or procession was held at every chapel, no matter how small, on the saint's day of its worship. People flocked in from the surrounding area and even from remote regions, in the case of renowned pilgrimages.

The popular musicians (dulzaina players, accordionists, violinists, ...) also came to these events as it was an important source of income for them.

In some cases, the placement of the musicians was regulated by the constable (representative of local authority). On other occasions, however, the musicians themselves probably chose the place they liked most, depending on the spots which were available and unoccupied by other musicians.

Some dulzaina players used diverse methods (such as finding a small promontory or standing on a bench or a barrel) to situate themselves in higher positions and thus observe and watch over the people who were dancing.

Once the musicians began performing, "corros" or circles of people gathered round them to dance. As they did so, the collectors carried out their task of approaching the men in the couples and demanding the amount to be paid for the dance (the amount was for a "saio", which included the jota, the porrusalda and the martxa).

When the pilgrimage, which usually lasted from four to five hours, had finished the dulzaina player and his accompanists gathered in the tavern to split their earnings.

Musical repertoire

The musical repertoire of the Vizcayan dulzaina players (or at least what has survived to our days) includes the songs which could be danced to in the pilgrimages. There were basically three: The jota (of ternary time), the porrusalda (of binary time) and the martxa (in six-eight time).

The dulzaina has also been used to perform a great deal of pasodobles. Most of the melodies were performed in tones which were "natural" for the dulzaina. For example, DoM, Lam and Sol M, with some played in FaM (although the Sib which corresponded to it did not have an ear-pleasing result). They rarely used DoM, when Si, Mi and Lab were achieved with the same fingering by altering the modulation of the mouthpiece. Both the jota (of ternary time) and the porrusalda (of binary time) are comprised of a series of three parts; the first two have sixteen bars (usually eight repeated twice) and a longer third part, called "Kopla", "Baltseo" or "Agarraue".

In this part, in which copla verses were sung (thus the name "Kopla"), the music was slowed and couples danced something similar to a waltz ("Baltseo") while holding hands and remaining close ("Agarraue"). During the dictatorship of General Primo de Rivera (1923 - 1930) close dancing was prohibited, which eliminated contact between sexes, an important part of the pilgrimages.

The music which you can listen to is from the songs performed by the dulzaina player Simeon Iragorri (Usansolo) in Iurreta during the Trikitilari Eguna on October 4, 1981.

PURRUSALDA / JOTA / MARTXA

The dulzaina players of Vizcaya have always played by ear, having learnt from others before them. The repertoire gradually grew, passed on orally from generation to generation, after listening to the songs which other musicians played at the pilgrimages. The dulzaina player then practiced them alone and later played them in other pilgrimages. This has led to a personal touch added to every song by each dulzaina player, so the same melody can have different interpretations or ways of performing it.

The men

Dulzaina players

The dulzaina players have always been people linked to the rural world, especially sheperds or coalmen. This left them plenty of free time to practice the instrument and make the fitas, which are essential parts and need time and tranquillity to be made as it is a difficult task.

Amongst the oldest known dulzaina players we can mention: Gillermo Alberdi "Aiusti" (c1870-c1930) from Aulestia (Vizcaya), although he lived in Bilbao. Demetrio Artetxe (1887-1933) from Zornotza (Vizcaya), who lived in Bilbao. He was the maestro of several dulzaina players of the next generation. Of robust physical constitution, he played with enormous elegance and ease. Julian Azurmendi "Katxarrero" (1885-1930) from Abadiņo (Vizcaya). His nickname comes from the fact that his father-in-law was a cacharrero (tinker). He went to America with him to work this trade but soon returned to devote himself to what he really enjoyed, which was playing the dulzaina. Vidal Muguruza (1884-1966) from Orduņa (Vizcaya). Father of the dulzaina player Iņaki Muguruza and a contemporary of Demetrio Artetxe, who he admired greatly. They coincided in Bilbao, where Muguruza was working as a municipal guard.

Juan Aiesta (Bedia, 1893-1988) and Simeon Iragorri (Usansolo, 1903-1991). Photograph taken in July of 1983.

Juan Aiesta (Bedia, 1893-1988) and Simeon Iragorri (Usansolo, 1903-1991). Photograph taken in July of 1983.

A great many dulzaina players have come after them all over Vizcaya. Some of these players had performed in pilgrimages during their youth, while others have played only for their own enjoyment or for their friends.

Dultzainagileak

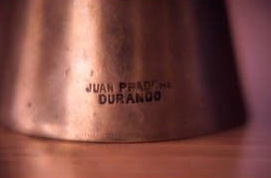

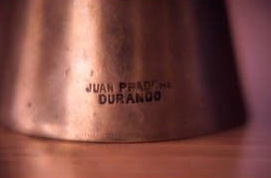

On the subject of dulzaina makers (aside from the current ones), most musicians from Vizcaya played with dulzainas made by JUAN PRADERE-DURANGO.

The mark of Juan Pradere - Durango on a Dulzaina

The mark of Juan Pradere - Durango on a Dulzaina

In addition, JOSE PRADERE, a brother of Juan who lived in Mondragon (Guipúzcoa), Jose Sodupe "Montte", from Azkoitia (Guipúzcoa) and Egiguren, from Azpeitia (Guipúzcoa) were other makers, though their instruments were not frequently seen in Vizcaya.

Except for "Montte", these makers died at the beginning of the 20th century, leading to a scarcity of instruments. The dulzaina players thus had to get by through the purchase and sale of existing instruments, as well as making copies of the originals themselves at times.

The decline of the dulzaina in the 20th century

In spite of this instrument's importance at the beginning of the century, afterwards it suffered a progressive decline from which it has not recovered. This was brought on by the following factors, amongst others:

- The death of the PRADERE dulzaina makers without anyone to substitute them. The direct consequence of this was a scarcity of instruments, which had to be purchased or traded with other players who owned them (there were even instances of an instrument being traded for a bottle of wine).

- The introduction of the diatonic accordion, or "trikitrixa" in the pilgrimages. This instrument, which had broader musical possibilities than the dulzaina, began to gain ground on it.

- The civil war was an important setback for the dulzaina. A lot of instruments disappeared, making the first problem mentioned even worse. Likewise, many dulzaina players stopped performing at this point.

- The customs in the pilgrimages began changing. Instrumental groups such as jazz bands began displacing previous instruments such as the dulzaina.

The current situation and future perspectives

Nowadays the disappearance of pilgrimages, changes in the form of entertainment, the death of most of the traditional dulzaina players and the rising popularity of the pipe of Navarre have led to a situation in which the dulzaina of Vizcaya is almost completely displaced.

Current perspectives for the recovery of the dulzaina of Vizcaya are based on different courses of action:

- conservation of the repertoire carried on by the traditional dulzaina players.

- making tuned instruments with improved fitas.

- the integration of the dulzaina in musical groups or bands with a folk or similar repertoire.

- the integration in other folkloric events, such as dance groups, passacaglia with giants or gatherings of pipe and dulzaina players.

Any of these courses of action should take the history of the instrument into account, although remaining rooted in the past could lead to a fossilization of the instrument. The balance between these two complementary stances could well define the dulzaina's future in the 21st century.