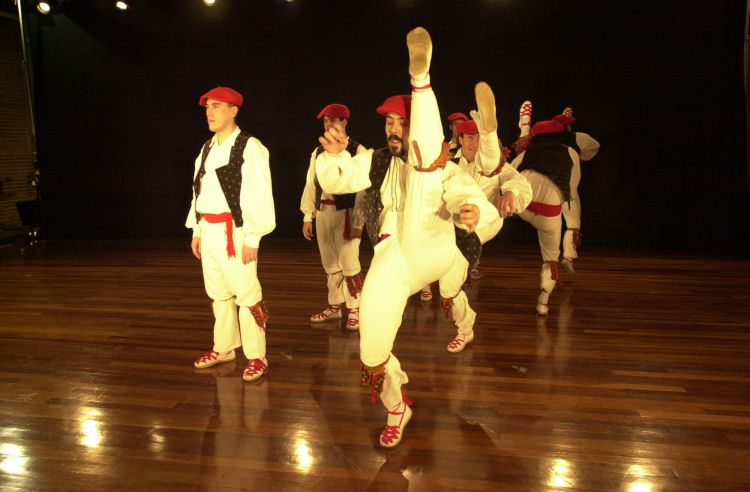

Dantzari Dantza

The Dantzari Dantza is a sequence of dances peculiar to the Duranguesado or Durangoaldea de Bizkaia, a region with abundant mythology, ancestral beliefs and a traditional economy based on merino sheep-raising farms and agriculture, apart from this, it bordered on the former kingdom of Navarre during the Middle Ages, and has wealthy mansion houses and defensive towers characteristic of this medieval period.

Regarding the before mentioned choreographic sequence, the different authors do not agree about the dances that form it, nor about their origins and even less about the sequence that they should be in.

In any case, we have an introductory dance with the waving of the flag over the heads of the dancers (Agintariena); a series of dances nominally related to the dancers who take turns to show their skills (Zortziko, Banako, Biñako and Launako), a play of weapons (Ezpata Joko Txikia, Ezpata Joko Nagusia and Makil Jokoa), and, at times, a dance that seems to represent death and, in that case, the resurrection of one of the dancers (Txotxongillo). This brings us to the Soka Dantza, a mixed circular dance that is performed anti-clockwise, the Fandango or Orripeko, Arin Arin and, finally the Biribilketa (or Street Runner).

However, we also have evidence of several dances which have either disappeared from the repertoire or have been readapted, such as the Hirurco mentioned by HUMBOLDT, of doubtful existence because of its structure, dances of bucklers or shields such as Platillu Soño; dance with bows, such as Uztai Dantza or Arku Dantza and even the Gorulari, recently recovered, and which was performed at the Fiestas Euskaras (Basque Festival) at the end of the 19th century; dances with ribbons or Zinta Dantzak, also known as Domingillue and already performed in 1828.

Finally, it cannot be denied that the dances such as the Soka Dantza, the Orripeko or Fandango, the Arin Arin or Porru Salda, and the Biribilketa, in spite of being performed independently of the Dantzani Dantza, have an important and necessary role in this.

At present we can see the traditional performances in Abadiño, Berritz, Garai, Iurreta, Izurza and Mañaria, though as can be seen in the previous lists, they originally must have been more widespread (Elorrio, Durango, Zornotza, etc).

Clothing

Iñaki IRIGOYEN (in Bizkaiko Dantzak, published in the Revista Dantzariak, special edition number 1, 1978) offers us the following descriptions of the garments used when dancing the sequence of the Dantzari Dantza, in the case of Abadiño, he says: "On the eve of the feast day a tree had to be placed in the middle of the square, this function was entrusted to the dantzaris. They wore their plain clothes, which consisted of a beret, gerriko and hempen sandals tied with red ribbons, while doing this."

The beret, the corset (gerriko) and the footwear are red or have red ribbons, however, if the dantzari is in mourning, or his companion is, they are black. On the day of the big festivity the dantzaris will appear in the square in all their finery, red beret and gerriko, white shirt, trousers and socks, white hempen sandals with red ribbons and a waistcoat.

J. L. DE ETXEBARRIA, in Danzas de Vizcaya (editorial Vizcaina, Bilbao, 1969) describes the clothing as follows: "On the morning of the big day, the eight dantzaris assemble at the Town Hall, attired in a shirt (with the sleeves rolled up), trousers and socks, all white, hempen sandals of the same colour (these are adorned with red ribbons, crossed over at the top, so as to be able to tie them around the lower calf) and with a red gerriko (corset) and txapel (beret) (...)".

The author adds two annotations to the previous paragraph, the first refers to the shirt, the second, to the colour red which in time of mourning is black, as already pointed out above. Let us see the note relating to (regarding) the shirt: "The ezpatadantzaris of fifty years ago wore their shirts with the cuffs fastened, and the neck of the shirt, which was collarless, fastened too. To this I must add that, at that time, and apparently in the district of Abadiano (many famous dantzaris were from here), apart from the before mentioned garments, they also wore a dark waistcoat with no sleeves, which according to some was adorned with three big silver buttons on each side of the breast and, according to others with three zitzarris (cascabels, small bells)." In his article Danzas de Vizcaya (Revista Dantzariak, number 3), Iñaki IRIGOYEN adds yet another fact on how they dress, he refers to a flower, the Immortelle, in a buttonhole of the waistcoat.

Apart from the descriptions mentioned we must also take into consideration the use of leather bands (clasps) with bells attached, which are tied to the calves of the dantzaris in the exhibition of the Dantzari Dantza, and which are removed for the later dances, such as Gorulari, Domingillue or Soka Dantza.

Implements

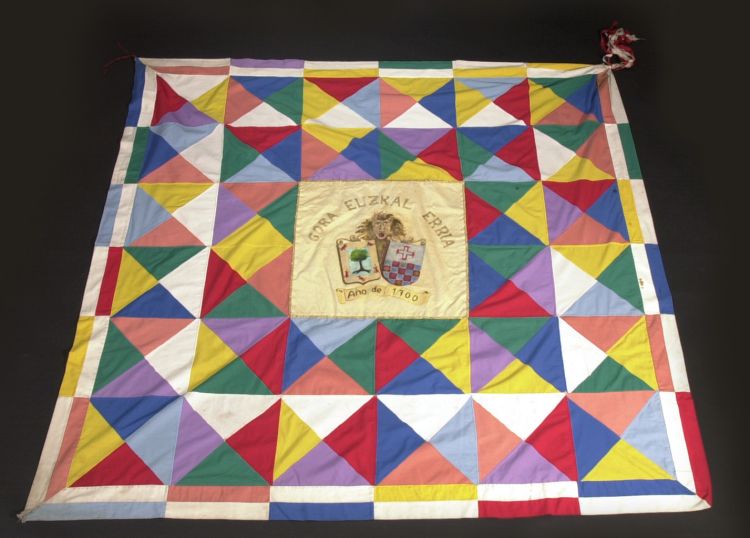

The flag

The flag, as Juan Eduardo Cirlot points out in the Diccionario de Símbolos, and Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant in the Diccionario de los Símbolos, is a totemic insignia that you put on a mast (as) a symbolic protection of the group. It is, at the same time, the symbol of authority, assembly and the leader. It therefore implies a cry for protection that Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant summarize as: "The bearer of a flag or standard lifts it over his head. He is, in a way, crying out to the heavens, creating a bond between heaven and earth". The flag or standard brings us closer to the existing bond between the symbol, its bearer and those acting in its name. Maybe here we could find a way of interpreting the salute to the flag that is performed in the Dantzari Dantza.

There is a dance among the Biscayan dances peculiar to the Duranguesado called Agintariena (literally "the one of those who give orders or command") in which, after saluting the standard and returning to the initial position, the standard- bearer takes off his beret and waves the flag above the heads of the rest of the prostrate dancers.

Well-known international scholars of Basque folklore, of the category of Violet Alford, have acknowledged that they do not know the origin and symbolism of this action, but, however, they mention the anecdote of a Romanian group that was dancing and jumping without stopping at the beginning of the century until they arrived in London where they were to perform an exhibition. In this exhibition, the flag had to be adorned with some special plants that made the dancers go into ecstasy or a mystical trance, but, as these could not be found on the island, they could only act and not really dance in the way they did in their village. This case can illustrate the magical use of the standards.

Julio Caro Baroja also refers to some dances peculiar to the Iberian Peninsula in which the ensign serves as a protective bond with the local divinity. These facts make us wonder if something similar might not occur in the case of the Dantzari Dantza, that is, that the dance of the salute to the flag could well conceal a call for protection, an attempt to communicate with the beyond, with the spirit (in La Rioja, as in other places, flags are carried in ecclesiastical processions).

However, the waving of the flag could well correspond to a very different function, which is that of presenting arms to the political- military standard, in order to prove to the authority the submission of the armed population in case of war. This would conform perfectly to the fact that as it was dealing with a population spread out in different settlements and as it lacked a legally established official militia until well into the 19th century, it was the commander-in-chiefs of the district who had to establish a day to inspect the troops in their charge. This would imply emphasizing the military function of the dances of weapons. Nonetheless the fact that these parades take place in different places and on different days in the same valley, as well as the fact that there exist other interpretations just as plausible as this one means that we should be wary of coming to any hard and fast conclusions.

Thus, we are not going to deal here with the symbolism and hermeneutics of such a dance, a question that is dealt with in more detail in the independent articles, and we will leave the interested reader with the opportunity to explore these questions.

The Sword

The sword, with its hilt and cutting edge, has symbolised many different things at different times in European history, from the honour and virtue of the Medieval knight who shunned the pleasures of the flesh (Tristan and Ysolde) to the very concept of chivalry personified in the bitter struggle against evil, the dragon or the Beast. It has also been a symbol of Christianity, because of the cross shape formed by the quillons, and before that symbolised Mars, the god of war and agriculture. It can therefore be seen as a tool used to ward off the forces of evil or the enemy, whatever his nature.

As a metal instrument the sword stands in contrast to trees and vegetation, and forms part of a masculine environment where the latter are associated more with feminine aspects, along with - for instance - the spindle, as referred to by Marius SCHNEIDER and later Juan-Eduardo CIRLOT. Curiously, the ezpata-dantza or word dance of the Duranguesado area of Bizkaia is linked to the feast of St. John, marked by dancing around a tree, and to images of late 19th century spinners. It is a dance in which the women, whose steps are usually associated with movement and generation, remain still in sharp contrast to the mobility of the male dancers, whose steps are firmer in philosophical categories, as demonstrated in the Soka Dantza and the Aurresku danced in church porches in the Duranguesado and other regions.

Leaving aside such areas as their magical functions, etc. (for information on which readers are referred to the works of J.G. FRAZER) sword dances come in a wide variety of forms in different places. Some are danced by individual men, who show off their skills at weaponry, and some by women who symbolically add their weight to their husbands' war parties. Such dances are seldom found in Bizkaia, or indeed anywhere in the Basque Country.

Before going into forms and developments in sword dances in Bizkaia, two points should be looked at which have sparked off discussions throughout the 20th century, and indeed continue to do so.

First there is the supposed development in the figures and instruments used, which led Curt SACHS to put forward the hypothesis that clapping to mark time developed into the use of short sticks - evidence for this can be found in Bizkaia in clapping and hand games and the Zaragi Dantza danced at carnival time in Markina and Ondarroa, and in other regions of Gipuzkoa and Nafarroa, where movements similar to clapping above and below the legs are made with small sticks. From there the next development could be long sticks or clubs.

Subsequently, in the view of some authors, clubs gave way to swords or poles, and finally to bows. Similar structures of dances with clubs and swords (Makil Jokua, Ezpata Joko Txikia, the Gernikako Arbola Dantza in Garay and Ezpata Joko Nagusia), or with swords and bows (Xemeingo Ezpata Dantza and Lanestosako Uztai Dantza), can also be found in Bizkaia. There are, however, other dances which do not seem to be related to the above, and which pose more of a problem for researchers, such as the Zortziko in the Dantzari Dantza and the Txotxongilo from Iurreta and Berritz.

The second point concerns the original significance and function of these dances. Different authors have given different interpretations, ranging from those who see all sword dances as war dances to those who believe them to be fertility rituals, dances of initiation into communities of iron-workers, medicinal or shamanic rituals, or even initiation rites for young men. All these theories can be found in the articles to which we refer here.

The locations of these dances and the dates on which they were, and continue to be, performed may also provide interesting data for more detailed study, as may the structures which they have acquired around the province.

In Bizkaia, sword dances can currently be found in Xemein and some of the villages in the Duranguesado area. Historical records confirm that similar dances once existed in other areas bordering on the above, such as Lekeitio and its outlying Districts, and Las Encartaciones. These include mining areas, coastal areas and farming areas, some isolated from the rest of Bizkaia and some not, but each bordering on the others areas in some way in the complex layout of districts and areas within the region, and no single explanation of their significance can be given.

The dates when the dances were performed vary according to the dates of local festivities, so no firm conclusions can be drawn there either, and further research is needed.

Finally, some of sword dances in Bizkaia have features in common with those of other regions, while others have their own, unique characteristics.

There are dances in which the performers, in full battle gear, (though that does not necessarily mean they are war dances) present arms to the authorities or to a flag (Agintariena). The flag itself and other associated matters must be taken into account when considering their symbolism.

In others, the sword is carried by performers but not actually used. This does not seem to be the case outside the Duranguesado area (Zortzinango).

In yet others the sword is carried by some performers and raised at some points to form what researchers have called a "coffin" (Txotxongilo).

Finally, swords are sometimes also used to form archways beneath which authorities pass, which is seen by some as symbolising a request for protection, or to form a platform (known as a "rose") onto which one dancer then climbs (Xemeingo Ezpata Dantza). This is similar, though not identical, to other dances in Gipuzkoa and elsewhere in Spain and Europe.

However there are no dances here involving individual or group exhibitions of sword handling of the kind found in Eastern Europe.

Sticks and clubs

Being made of wood, sticks and clubs belong to the world of living beings in which the cycle of birth, growth, reproduction and death repeats itself on ever higher levels. The club and the stick thus represent cyclical time and perpetual renewal, so it is no surprise that Christ himself died on a cross of wood at what Mircea Eliade and other authors have called axis mundi, the centre of the world, a place which has its roots in the netherworld, its strength in the mortal world and its canopy raised to heaven. The club acts as a post or column which holds up the three levels of reality: the first subterranean and inhabited by unknown, perhaps malignant numens; the second at ground level, where the trunk bears witness to the passage of time; and the third heavenly, giving access to higher planes. The stick and the club, then, are routes into other realities. It is not by chance that the wood on which Christ was sacrificed can symbolise access to both hell, where he spent a short time, and heaven, where he sat at the right hand of his Father.

There is a striking contrast between the symbolism of sticks and clubs as wood, with connotations of new shoots springing up even from apparently dead stumps, and the cold, sharp steel of swords.

If the club represents fertility (albeit not clearly manifested), then the sword represents just the opposite, i.e. staticness. If the club is associated with female symbols, as ventured by DURAND in Estructuras Antropológicas de lo Imaginario (published in Spanish by Taurus), the sword represents rationality and purity of thought: it is a symbol of platonic, cerebral love dissociated from the needs of the flesh, as they would have said in former times.

These ideas may help us to reach an initial interpretation of the reasons for dances with sticks and clubs, and for dances with swords or daggers. Symbolically we can perhaps posit a juxtaposition between the two types of dance, but this does not suffice as an overall interpretation.

Leaving aside the general symbolism associated with sticks or clubs and with swords or daggers, perhaps it would be of interest to look in more detail at their use. Let us leave swords and daggers for another occasion and concentrate for the moment on sticks and clubs.

Short sticks and longer sticks or clubs have been used for many purposes over the centuries: as implements for digging, cleaning, sketching on the ground, making fire, defence, etc.

Folklore experts and early 20th century dance scholars make various points concerning the possible origins of these dances with implements.

Curt SACHS and some of his followers argue that the use of sticks in dances was a development from clapping dances, with the slap of hand against hand leading on to a similar movement of stick against stick and thus giving rise to dances with short sticks. This view may perhaps fit in with such dances as Zaragi Dantza ("dance of the wine-skins"), which is currently performed at Carnival time in Markina and Ondarroa. This point will be looked at in more detail later.

These authors argue that these short stick dances developed into dances with clubs, then swords and daggers and finally dances with bows, poles and other implements.

There is a group of dances in which short sticks are used in movements and figures similar to those of clapping dances. They sometimes feature movements which first speed up then slow down, leading them to be considered as rural dances representing farm work. Following this same hypothesis it is no surprise that small hoes or other implements should sometimes be used instead of sticks.

But small sticks were also used instead of daggers as weapons in the training of troops, often accompanied by small shields. The Trokel or Brokel Dantzak (as it was apparently known in the Duranguesado or Durangoaldea area of Bizkaia) seems to derive from this, though other interpretations are also possible.

Reputable scholars have also suggested that sticks and clubs represent something similar to magic wands in fairy stories, i.e. ways of bringing to light buried treasure. In an agricultural and pastoral society this is clearly associated with digging up tubers and plants hidden underground. This (in line with Violet ALFORD, Julio CARO and many other researchers) would make short stick dances agricultural dances or fertility dances.

Those who favour this interpretation and see sword dances as developing from dances with sticks or clubs have simply put forward the conjecture (Lucile ARMSTRONG) that since swords make more noise when they clash they can more easily awaken benign spirits and frighten off evil ones from crops (whether they be demons, witches or plagues of insects). Stick, and later sword, dances would therefore have the same purpose: to ensure the sustenance of the people.

But short sticks have also been used for other purposes: e.g. instead of sashes (gerriko) laid on the ground in the dancing game of txakolina, in which the dancer, after drinking a certain amount of alcohol, must skip alternately through the four segments formed by two crossed sashes (gerriko), as described by Resurrección María de AZKUE. In some dances in the Pyrenean areas of Nafarroa they are also used as supports to help dancers keep their balance.

Before looking at dances with clubs, it is worth mentioning the myth, recounted by Josemiel De BARANDIARAN in Mitología Vasca (published by Txertoa), of the man who, searching for the end of the world, came to a place where the sun was raised by beating against the rocky peaks with clubs.

Although this myth tells us that we cannot reach the end of the world, it also reflects the popularly held belief that the sum was lifted up above the earth, and that this was done by men beating clubs against the rocks. This idea that the beating of sticks or clubs (one against another or against other objects) is needed to raise the sun points us in the direction of interpreting club dances as sun-worship rituals which seek to ensure by magic that the sun will rise.

Like stick dances, club dances would therefore be fertility dances, though other purposes may also have been involved in some of them.

How should we interpret the Makil Joku? There is for the moment no direct or indirect evidence as to its origin, but we can at least put forward some possibilities.

Small bells

Symbolism of the hand bells: Many authors such as Curt SACHS, Violet ALFORD, Lucile ARMSTRONG, Juan Antonio URBELTZ, Marius SCHNEIDER or Juan Eduardo CIRLOT agree in their interpretation that the hand bells are implements or instruments that "are supposed to have prophylactic powers against misfortune" and as such were used by those devoted to Dionysus, the medic men in Africa, and the Callicantzari in Skyros. This could put us on the right path to an explanation of their use in the dances of swords, such as the Dantzari Dantza, being therefore dances with a strong ritual context bound to Nature and its spirits. However, that the spirits that they want to frighten off are only of a rustic nature, or that they refer only to the dead or other images of a numen is going to cause a lot of controversy and arguments that will be heightened in our case, by the symbolism of the dances with swords.

On the other hand we cannot ignore their simple and direct function related to keeping the rhythm of the performances. The sound of the bells could well have had the role of making the dancers keep to the rhythm of the dance.

Music

All the experts on the subject of the Dantzari Dantza (Iñaki IRIGOYEN, TILIÑO, Juan Antonio URBELTZ, K. DE HERMODO, etc.) coincide in asserting that the exhibition is performed to the sound of the Txistu and of the tabor, although the Silbote can also be used, which, although belonging to the family of the flutes or wind instruments, is longer than the former, and the kettle-drum, which unlike the tabor, is shorter and wider, besides which its percussion is made with two drum-sticks and not with just one, as happens when the musician plays the Txistu and the tabor at the same time.

The Silbote, Txistu and Txirula are the three musical instruments belonging to the family of the three-holed flutes, which we find in the Basque cultural region, and it is the first two that are used in the folklore of Bizkaia.

The first, because of its length, needs to be held in both hands, thus, while the right hand keeps it steady, the left hand holds the weight and regulates the tone. Owing to the length of the instrument it has to be transported in two separate pieces, which fit together, and this is also the reason why the musical scale is lower than in the Txistu. The notes come forth depending on the positioning of the tips of the different fingers, in the same way as in the smaller version.

The second instrument, the Txistu, shorter than the Silbote and longer than the Txirula, is used as the basis for (of) the traditional music of Bizkaia. Like the other two, it has three holes, plus the end of the pipe, where the little finger is placed, to register the sharp and flat notes.

The Txistu is usually accompanied by a drum or tabor, which is a resonant wooden box, higher than it is wide, whose ends are covered with a leather skin (nowadays with plastic), stretched to several different tensions. The tabor is played with the right hand by striking with a wooden drumstick. Apparently in IZTUETA's time, or even beforehand, the sound of the drum was preferred to the whistle, something that has been changing gradually up to the present time, in which the tabor is hardly heard.

As has been mentioned, the combination of the Txixtu and the tabor has been accompanied, on the one hand by second voices of the Txistu, on the other, by the Silbote which can reach even lower scales and, finally, by the kettle-drum (or box of double drum-sticks). It is impossible to put a date on the origin of the instruments, especially since the finding of a perforated bone in a prehistoric room at Isturitz, to the north of the Pyrenees, but inside the present Basque speaking region, appears to indicate the creation of similar musical instruments at a time unknown.

We recommend the Enciclopedia Auñamendi encyclopaedia, with a website on the Internet at eusko-ikaskuntza.org for those who wish to explore the subject of the Txistu in more detail, above all relating to the description of their manufacture and handiwork, and also an analysis of the traditional duties that the taborer or drummer, nowadays called the Txistulari, fulfilled.

It is noteworthy that, in general, it has been men who have been in charge of this duty perhaps due to the fact that they strike the drum with the drumstick, whereas women traditionally do it directly with their hands or fingers. However, the Enciclopedia Auñamendi mentions a case, dated 6th May 1611, in which, according to the records of a lawsuit for witchcraft, it appears it was a woman who was playing the tabor in Hondarribia.

It is also interesting to note that the taborer or Txistulari had a wide range of different duties. He was the chief, and charged a fee, not only at festivals for the amusement and enjoyment of the people, but also at funerals, weddings, times of disease and sickness, calls to war or to fishing expeditions, etc.

History and Geography

But in the case of the Dantzari Dantza dance cycle, which is typical of the Duranguesado or Durangoaldea area of Bizkaia, there is an added obstacle: each dance in the cycle must be investigated individually in each of the towns and villages where is it is still performed, and historically in all those with which it may be related in some way.

We must therefore be cautious when it comes to drawing up a chronology. We must also bear in mind that these dances originated in an uneducated society where writing was not a normal form of communication and ideas were not set down in words until relatively recently. The Basque language did not find its way into print until very recently, so any references we find to dance performances are either recent, as is the case of the work of Resurrección María de Azkue and other 19th and 20th century ethnographers and ethnologists, or take the form of account books at town halls and provincial council buildings or at churches, these being the only places where written records were kept.

Historical data on dances in a chronological sense can be found in these account books, but it must be remembered that they are only records of income and outlay, and therefore generally go no further than to state how much is spent and on what. They give data along the lines of "in village X o date Y, association A spent B on festivities" and go into no further details, leaving the reader to imagine as best they can just what is meant by "festivities". The date of the festivity is usually recorded, thus giving an idea of what was being celebrated and sometimes enabling comparisons to be made with current events and reasons for expenditure. If money was spent on bells (to give a frequently found case) for festivity X, and there is a current celebration around that period which involves the use of bells, it is still no more than a bare assumption that financial outlay at one period and at the other goes on the same articles: there could be other dances and displays with bells apart from those we are looking for. Compiling historical data is a truly laborious task which calls for great patience. Yet another difficulty is that the written data which we must use as our sources may well have deteriorated and become blurred or torn over the years before they come down to us.

There is also a third source of information which is not based on past or present practitioners of dances, but rather on the accounts of travellers. Such people cannot be taken as completely reliable witnesses of the events that unfold before them, but what they write about things they saw or heard on their travels in relation to particular dances may still be used if researchers can tie it in with particular performances in terms of form, date, type of celebration, instruments used, etc

In short, there are various ways in which we can approach the establishing of a historical context for a dance:

- comparison with similar dances elsewhere, though comparative analysis is currently not favoured.

- accounts of travellers and researchers from years gone by, who may refer more to what type of festivity was celebrated rather than to what specific dances they witnessed.

- account book entries referring to expenses for the purchase of material needed for a performance

- accounts by people who danced or created new dances at specific times - many such people knew how to write and set down the origins of these dances in publications or diaries.

- and detailed accounts of how, where and why dances were performed, written by their creators. Such accounts are certainly not often discovered.

To state, for instance, that the sword dance originated in a particular period is merely to air speculation and belief. Nor is there any logical basis on which to compare dances in Bizkaia with those from other areas. Some accounts of travellers may be reliable, but others have little to do with reality: for instance HUMBOLDT's reference to the hirurco may based on be nothing more than his own learned assumptions. Dancers, past and present, may be experts in their dances, but their expertise does not stretch back far enough to include any knowledge of their origins. And finally, those who are capable sincerely of recording changes introduced, as in the case of J.L. Etxebarria's work on Basque dances or the contests to create new dances which were so much a feature of the 19th and 20th centuries, give no indication of the origins of the dances resurrected, changed, created or re-created. All this means that any interpretation seeking to determine their true origins is plunged into chaos.

The only path open to us, in spite of its limitations, is to analyse the dates which are available in written historical records. The work of Iñaki IRIGOYEN has been of inestimable service in this task: with infinite patience he has compiled data on performances from the historical records of different towns. His studies and those of his followers, although restricted to entries in account books, have provided us with a calendar of festivities involving dancing, which is not to say that the dances mentioned were not danced before the dates on which they are first mentioned or in different ways.

In the case of the Dantzari Dantza in Abadiño, Berriz, Garay, Iurreta, Izurtza and Mañaria, IRIGOYEN's data include entries dating back to 1676 in Iurreta of payments for dancing on the feast of St. Michael. Dances are still performed on that date, so this may serve as a reliable first record of such performances. After the initial record dated 1676 the feast of St. Michael in Iurreta is mentioned again in 1679, 1685, 1687, 1688 and 1690, though no overall explanation of the performance is given. So while we can venture to state that the Dantzari Dantza or some other dance was performed in honour of St. Michael in the 17th century, we cannot affirm that it was similar in order or in the manner of its performance to the dances staged today.

In 1615 payments are also recorded for the festivities marking St. Peter's day in Berriz. Such payments are also mentioned in 1662 and in subsequent years. This indicates that the feast of the Apostle was important in the early 17th century, but certainly does not indicate that it was important before that time or that the performances involved were similar.

We have been unable to obtain information from the other towns where the Dantzari Dantza is danced now or has been danced in the past. That does not mean that such information does not exist, but merely that we have not been able to obtain it.